Growing Up With PMDD Before I Had the Words

I was raised in a world that taught me pain was womanhood. Not explicitly. But it was there. You bled every month. You put up with the pain. You managed. You got on. That is what made you a woman.

Before I Had the Words

At school, we were taught about periods the way we were taught about photosynthesis. Diagrams and disclaimers. We learned about hormones. The menstrual cycle was a neat biological loop, complete with tidy colour-coded graphs and medical terms that felt detached from real experience. You bled, you ovulated, and then it repeated. What it felt like to live inside a body ruled by this cycle? Irrelevant. It wasn’t about us. It was about exams. And so I memorised facts but never internalised what they meant for me.

I had no sense of what was normal. No idea how badly it could go. No language to say: this hurts more than it should.

As a teen, the cramps took my breath away. If they started at night, I curled around a hot water bottle with paracetamol and counted the hours. But the pain would be so intense I couldn’t sleep. If they hit during school, I’d squeeze a friend’s hand under the desk or grit my teeth and deal with it alone. If I ever mentioned the pain, I was told, this is just what periods are like.

The physical pain was only half of it. In the days before bleeding, my mood swung hard. I snapped, cried easily, and felt alien in my own skin. At home, I felt like a volcano, always ready to erupt. Angry at everyone, desperate to be left alone. Half the month, I was myself. The other half, I wasn’t. Eventually, the pain became a part of my life’s background noise — loud, but expected.

Then there were the thoughts. Dark ones. Really dark. Something harder to say out loud. I would think things I didn’t want to think. I would imagine disappearing, or not waking up. And every time, I told myself it was just stress, or just hormones, or just me being dramatic. But it wasn’t. These weren’t just passing thoughts. They were invasive, persistent, and they came every month. And I was terrified to say anything. So I carried that silence too. I hid the truth about what it felt like to be wired this way. About how terrifying it was to feel like your mind was working against you. It didn’t just disrupt my mood. It pulled me into a dangerous loneliness, one where I didn’t even feel safe in my own thoughts.

But I didn’t know how to say what I felt. So I didn’t.

Instead, I blamed myself. For being irritable. For snapping at my siblings. For the way I cried over everything. For the thoughts that consumed me. And once this phase passed, I apologised a lot. I made duʿāʾ even more. I begged Allāh to make me calmer, kinder, easier to love.

Between Faith and Hormones

As a Muslim woman, I was also so conscious of my character. That my akhlāq and adāb are pleasing to my Lord and to those around me. So when my behaviour felt out of control, so did my īmān. I thought I was failing mentally and spiritually. I feared my anger was a sin, my inability to “just be patient” meant I was weak in dīn. No one ever told me it might be medical.

It wasn’t until my early twenties, when I began studying health more seriously, that I stumbled across the term PMDD: Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. I was reading about women who felt like they turned into someone else every cycle – a “monster”, they would say (though I don’t like using that term). They were irritable, anxious, despairing — then clearing within days of bleeding. It sounded too familiar.

I began tracking my symptoms properly. I noted moods, sleep, appetite, and energy. I made lists. I watched the pattern form: every month, like clockwork, the same descent. Tearfulness. Rage. Despair. Then, once bleeding began, it lifted, as if nothing had happened. It was the cruelty of the clarity that followed that made it worse. With months of records, I went to my GP. I spoke plainly. I showed the data.

Finally, A Name for the Pain

At 23, I was diagnosed with PMDD. The diagnosis didn’t “fix” anything, but it gave me language and a map. My body wasn’t failing me; it was signalling loudly that it needed care.

I trialled a pill; my side effects were awful, so I stopped. That didn’t mean there were no options — it meant I needed a different plan. I learned that treatment is a process: start, assess, adjust. I’m still figuring out what balance will work best for me. But the difference now is that I’m not lost in the dark anymore. I know where to look.

Learning to Live With PMDD

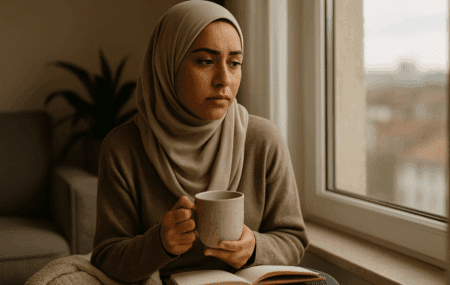

PMDD still affects me. But I meet it now with awareness. With softness. I plan around it. I protect my relationships. I advocate for myself with doctors. I listen to my body and treat it with more compassion than I once thought I deserved.

Though truthfully, it should not take a woman bleeding, breaking, and burying her own shame to earn a diagnosis. Unfortunately, for too many of us, it still does. I spent over a decade believing I was just difficult. PMDD can be debilitating, and yet, it’s still unknown to many, including the very people it affects.

So, I wonder. Had I been taught earlier about menstrual literacy, perhaps I would have navigated my teens and early twenties with far more grace? With far less shame. Because there is nothing immodest about understanding your body. There is no contradiction between īmān and informed care. Islam encourages knowledge, especially when it enables healing. The Prophet ﷺ said, “Seek treatment, O slaves of Allah! For Allah does not create any disease but He also creates with it the cure, except for old age.” Our health matters. And we must start saying that more often.

If this story is yours too, you are not alone. You are not weak. You do not have to carry it in silence. May this pain become a path to wisdom and gentleness — for me, and for those who come after.

This anonymous entry is the intellectual property of its author and is protected under copyright law. It may not be reproduced, distributed, or used in any form without prior written permission.